Three members of the Bad River Tribe discuss how their response to the opioid crisis emerged from determination, a desire to help, and a commitment to Ojibwe teachings.

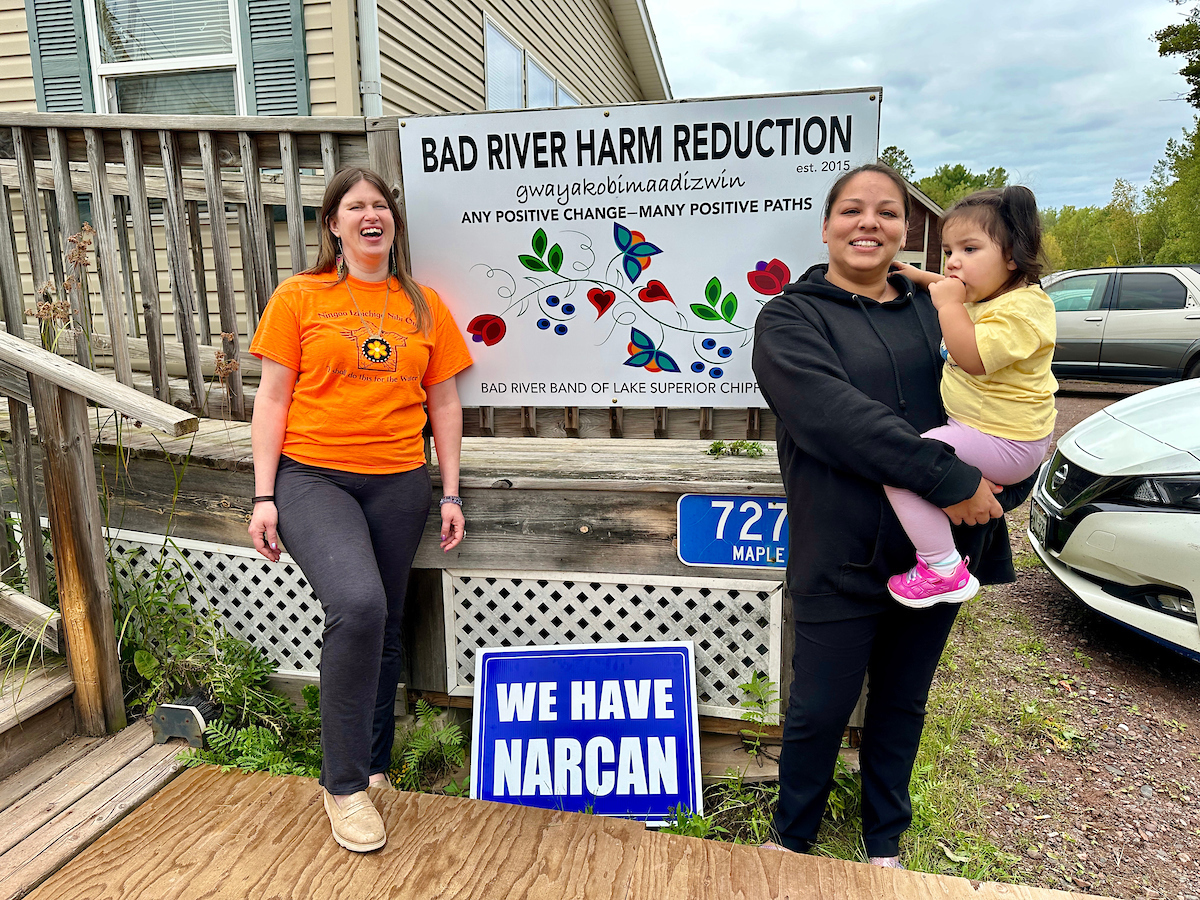

Since 2015, the Bad River Tribe has offered harm reduction services and supplies for people who use drugs in their community and throughout the state. The program, which launched from the desire to do something to address the opioid epidemic, strives to save and rebuild lives by serving those affected by addiction, confronting the discrimination endured by people who use drugs, and advocating for more humane law and policy.

Program founders and leaders Aurora Conley and Philomena (Phoebe) Kebec and peer specialist Eli Corbine gathered to share how far their work has come since they began, the obstacles they face, and their hopes for where it might grow next.

(Some of these themes are also highlighted in the powerful documentary film, Bad River, which opened in theaters nationwide this spring and tells the story of the tribe’s efforts across generations to protect their land and water.)

"It was an act of love and service that we set out to do. If it was just listening to folks sitting there and trying to understand their situation or whatever it might be, then that was a great start. But I can't believe where we are now. It’s a great and beautiful thing to watch our growth, the same as it is sad because everything has an opposite," explains Aurora Conley.

Responding to a crisis: “We were sick of seeing people die.”

Aurora Conley:

When I speak about our experiences in harm reduction, it is personal. I had a relative who I discovered was injecting, and I'm a trained first responder. I've been for the last 20 years. So, I have a little bit of medical background, and knowing that she was reusing rigs — they were using heroin — they were doing a lot of things that seemed scary. I grew up here. A majority of the folks that are our clients are my family and friends. So, I think I took it a little personally and trying to find something to help us.I distinctly remember asking Phoebe, freaking out about the overdoses we were seeing, “Isn't there anything that we can do? Isn't there something? Isn't there a medicine that can reverse it?” I'm thinking like in the movie “Pulp Fiction.” I had no clue.

I also remember the day she walked in the office and said, “It's called naloxone.” And I jumped up. What does it do? Where is it at? How do we get it? And she said, “That's all I know.” And I was like, well, let's go. It seemed we should just have been able to extend our hand and say, yeah, we need it. But, oh, my, that was not the case back in 2014. I wrote tons of emails to as many folks as I could reach across the country in hopes to find it. It took us a year to get naloxone in. It was so tough. It was so underground. It felt like that nobody would talk about it.

Phoebe Kebec: The knowledge related to harm reduction came to us organically. We were willing to do the work to make it happen without the real support that we needed because we were just sick of seeing people die. And we continue to be sick of seeing people die.

There was a shift that happened between 2011 and 2014. When I moved home in 2011, it was pills, and that was what everybody was using. And then it changed abruptly. People that had been using pills were injecting. And that shift took place over just a couple of months in about 2013. And then we had some people pass away of overdoses. The overdose fatalities started to ramp up in 2014.

I think that was when we first started distributing naloxone in the community. There were a lot of people who thought we were crazy, that we wanted to give people needles, but we also paired it with overdose prevention training.

"It took us a year to get naloxone in. It was so tough. It was so underground. It felt like that nobody would talk about it," Kebec remembers.

Aurora Conley: The first few years were really tough. We knew that we wanted to help and that as smart, strong, indigenous women, we might have that capacity. We had to learn so much. We started with nothing, and to where we are now with staff and a building, it’s been a beautiful thing. Because what we're fighting against is hard.

We try to speak on the seven teachings of our culture and Ojibwe, but how do you incorporate seven teachings into the harm reduction? Well, first, we started with love. That's one of the teachings. And it's because we love people, we love this community, and we love each other. And that's where it started from. It was that act of love that Phoebe has so well scripted in our handbook.

It was an act of love and service that we set out to do. If it was just listening to folks sitting there and trying to understand their situation or whatever it might be, then that was a great start. But I can't believe where we are now. It’s a great and beautiful thing to watch our growth, the same as it is sad because everything has an opposite.

Bad River Harm Reduction staff (clockwise from front): Phoebe Kebec, Aurora Conley with her daughter, Connie Denomie, Lisa Whitebird, Kim Ford and Eli Corbine.

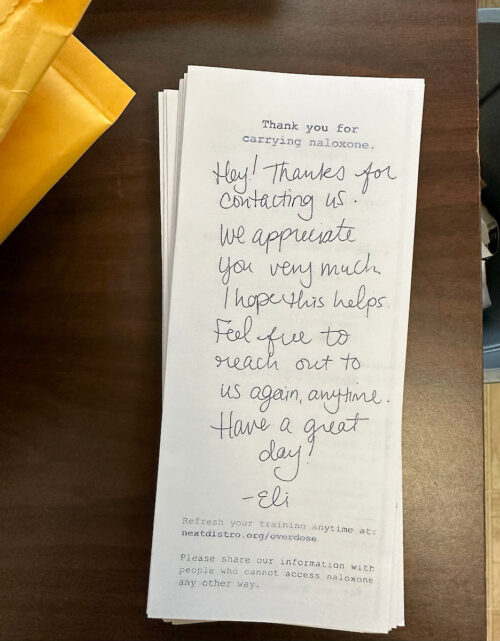

Where we are today: “What’s making a difference. . . is hyper-local work.”

Eli Corbine: I work as a peer specialist, offering peer support within the community and other services like food, bus passes, essential things that people might need to get to and from appointments and stay on that path of recovery. I serve about 3 to 5 people on a weekly basis, sometimes more, and that's just within the community that I see. We are always open to more people. In the mail orders, mailing out naloxone and Narcan, there are more. For instance, one day last week, I think there were 40 shipments. It varies.

Phoebe Kebec: What's making a difference in the opioid crisis is this hyper-local work that's being done by Eli and Aurora and others to create relationships with people and sustain those relationships through having a trusting experience. We're really trying to make that happen through this methodology that we've created that employs people that have had experience or are actively using drugs to be those service providers and those trusted key points. We're confident that that is an effective methodology. It's a lot more effective than having somebody who's kind of a professional and a little bit like one step removed from deploying harm reduction services.

We strive to provide options and choices for people in terms of distribution and getting resources out to people who use drugs. We also had to create this whole other public information around being naloxone-forward with helping people who don’t use drugs to administer it. In this last year, we've gotten the sheriff's department to allow people to bring their buprenorphine prescriptions and be dosed in jail, which is huge.

Another lesson that we learned is that there has to be redundancy in our HR (human resources) system. If you're going to run a harm reduction program, you have to have a built-in support system within your program because otherwise you're going to burn out your staff. Now we have a much more robust staffing model. We have a lot of contractors that are out in the field providing deliveries of harm reduction supplies and naloxone.

Today, we're kind of full circle. Aurora is still providing services, except now, instead of doing it for free on the side when she has time, she's getting paid for it. That's one of the nice changes that we've implemented. For Eli, too. This is a real thing, and we provide essential services.

Eli Corbine offers peer support within the community and other services like food, bus passes, and essential things that people might need to get to and from appointments and stay on that path of recovery.

The drive to secure financial resources: “It’s an equity issue.”

Phoebe Kebec: There’s this pernicious myth that all these government agencies have to do is provide naloxone and then it just magically gets in the hands of the people who need it. When it takes a tremendous amount of skill and effort and experimentation and developing partnerships with people who are using drugs to get that naloxone into the hands of the people who are going to use it to respond to an overdose and save someone's life.

There’s also this myth that what we do is free. And it can be – at a huge cost. Aurora and I did this for years and years without any staff support or compensation, but it almost killed us. There's an expectation that indigenous and black women and Chicano women for the most part are going to do this for free when there's tons of money coming into these public health agencies.

The State of Wisconsin reported $27 million in unspent FY20-21 State Opioid Response (SOR) funds from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in September 2021. Our program has only ever received Narcan from Wisconsin SOR funds. At this point, we are providing statewide overdose prevention services through our mail order program. This is a public service that we're providing. We have funding through Vital Strategies (a private foundation), but that funding is going away in two years.

We need the State of Wisconsin to understand that there are people like us who distribute and make sure that people are being taken care of down the supply chain, right? We are doing the hard, intensive work, and it's emotional labor along with physical and intellectual labor that takes place. We’re answering calls for people figuring out what they need, how we can approach them, and thinking about what the communication style is that will resonate with them.

And then we're dealing with life and death situations, and the worst outcome is always in the back of our minds. Somebody came to my house last Thursday night, and I gave him two kits of naloxone because that's what I had, but I should have probably given him five. The emotional labor that goes into every single interaction is part of what is not being compensated as work. At this point, our program is not being provided the kind of funding that we need for ongoing sustainability.

I think it's incumbent on state and federal agencies to recognize that there are people working on the ground that are being cut out of the money that is supposed to be going to them either through opioid settlement funds or other funding sources. And it's an equity issue. We can't do this for free. It's too big, and it's too much, and it's not right.

"It takes a tremendous amount of skill and effort and experimentation and developing partnerships with people who are using drugs to get that naloxone into the hands of the people who are going to use it to respond to an overdose and save someone's life."

—Phoebe Kebec

What’s next? Building tribal economic development through new approaches and leadership: “Just like with water protection.”

Phoebe Kebec: What's also needed in our community is a lot more opportunity for people who have been impacted by the opioid crisis to earn a living that isn't associated with drugs or isn't associated with drug sales whatever kinds of things that people do to get by because they don't have other opportunities.

There is an expectation that people are going to stop selling drugs when they have a record, but they don't have any documentable work experience and may not have a high school diploma. And that's unrealistic unless we provide support for them to engage in the legitimate economy.

In the next decade of Bad River harm reduction, we want to support people in diversifying their entrepreneurialism skills, finding and maintaining employment, and offering opportunities for professional development for the people we serve. Because now, as a society, we just send people off to jail and prison, and when they come back, we expect them to magically find gainful employment. but a decent portion are going back to selling drugs again.

Honestly, it breaks my heart. We celebrate returning community members. At first, they're doing great. But what do we have for them? I don't know. Some of the same people, months later, are back to square one, which makes them vulnerable to returning to incarceration.

We have to build a jobs program so that they have immediate opportunities to plug into positive activities – for pay. Meaningful involvement by people who use drugs, which is essential for the integrity of harm reduction, shouldn’t be token payments here and there, but should provide a pathway to living and abundant wages.

Eli Corbine: When there was a job opening for harm reduction here, I just went for it. It was a little bit different of a direction than I was at, and I liked it. I've only seen this type of camaraderie a couple of other places, which is really nice. And I like the message. The harm reduction program is helping us grow as people, as recovering addicts, giving us a professional light to be in, which branches out to help other people. I feel like we're all on the same team. We're all trying to have the same common goal. Sometimes it looks a little different from different ways.

I don't know everything. I've only been doing this for almost a year. But I've been in recovery for multiple years. I know that we need to learn everything we can about helping people with addiction. I see harm reduction giving opportunities and financial stability to a lot of people.

"We want to do this work. We need to do this work, and our people need this work. Just like our leadership in water protection, we can build it and show others how this kind of thing gets done."—Phoebe Kebec

Aurora Conley: We need their voices, too, and we need to utilize the skills that they've developed, the knowledge that they have. Through the peer support program, we provide a way to just accept you for who you are and that we need you on our workforce and that you will be paid for that. We're not asking you to volunteer. Although many of our clients probably volunteer in a community organization aspect, I'm sure they sit around and have probably exchanged information about us or their feelings or emotions about our program. And to me, the fact that they're even talking about it, raises the volume now on their wanting to be employed. The fact that we can employ folks and pay them, it's really beautiful to see some of our clients succeed.

Phoebe Kebec: I think this also speaks to a need for different levels of engagement. Some participants might not be able to do the harm reduction deliveries at this point, but maybe we could get them hired on to do overdose prevention trainings. And maybe there's other things that we can get them pulled in on that have more support built in. We have a lot of folks coming to our harm reduction drop-in center and helping out – sweeping floors and cooking a meal. It would be great to have a way to compensate them for these activities and provide diversified opportunities so that people can graduate up into areas where they can exercise their leadership and take on responsibilities as they kind of mature in the program. We're trying to think about the cutting edge of tribal economic development. It's good to be thinking about big fancy hotels and the latest and biggest things and engaging in tech, but we also need to think about the employment needs of those with a disability related to the opioid crisis.

I would like us to plug into the federal money that is coming around and other funding streams and use them to build up this leadership model that we're discussing. Because I think what Aurora and I are speaking to is an organic concept that's very much in line with what the Bad River community is all about.

We want to do this work. We need to do this work, and our people need this work. Just like our leadership in water protection, we can build it and show others how this kind of thing gets done.

Jennifer Roche facilitated the roundtable conversation and edited the transcripts.

The Bad River Harm Reduction home office greets visitors with a message of hope. Gwayakwaadiziwin means good character and honesty in Ojibwe.

Lisa Whitebird honors her grandmother, Grandma Eagle, who was born in 1948.

Program founders and leaders Aurora Conley and Philomena (Phoebe) Kebec incorporate seven teachings of Ojibwe culture into harm reduction. "We started with love. That's one of the teachings. And it's because we love people, we love this community, and we love each other. And that's where it started from. It was that act of love that Phoebe has so well scripted in our handbook," explains Conley.

The reservation’s conservation area contains almost 500 miles of rivers and streams, over 30,000 acres of wetlands, 38 miles of Lake Superior shoreline, and the Kakagon Sloughs.