Destiny Washington is Comer’s youngest fellow, a 17-year old high school student from Gary Comer College Prep in Chicago

As the Potanin Glacier came into view, the sun was already lowering in the afternoon sky. Nearing the end of a 10-mile rugged hike, 17-year old Destiny Washington walked along a horse trail that jutted up the landscape towards the field of ice. A few colorful tents were visible on the horizon, but she didn’t stop. Destiny trudged on to what would be her home for the coming days.

Destiny, a student at Gary Comer College Prep in Chicago, was traveling this past summer with the University of Maine’s Aaron Putnam deep into the craggy mountain range of the Mongolian Altai to the Tavan Bogd National Park. The park is home to the largest glacier in Mongolia, the Potanin, and it’s half a world away from her neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago—more than a week of traveling by plane, car, and hiking with pack camels. This was Destiny’s first trip outside of the United States. She was trying to determine how long it took the Potanin Glacier to retreat to its current location and test the affect that increased levels of carbon dioxide have on melting glaciers.

"Learning in the field is different from learning in the classroom. Out there, I get to experience what’s happening. In the classroom you have examples or demonstrations, but you don’t have the hands on feel of what is actually happening."—Destiny Washington

She was guided by Putnam, who led the team in collecting surface samples of granite boulders embedded on glacial moraines for exposure dating. Jessica Stevens, Destiny’s environmental science teacher at Gary Comer College Prep, joined the group as well. Stevens said that her role was to push Destiny and make sure that she was okay. “It’s great to work one-on-one with a student and really see them develop,” she said.

Putnam’s work in the Altai is an attempt to date the demise of the Ice Age in the interior of Asia and a part of a broader body of research being conducted by Comer-funded researchers globally. “It was my wish to bring students into this environment to experience that intersection of different elements of science and the natural world and experience it first hand, to learn what the field science has to offer,” Putnam said.

Putnam’s work in the Mongolian Altai has been supported by the Comer Foundation for several years. This year, he was also awarded an Early Career Award by the National Science Foundation. A major component of that grant is to help train the next generation of field scientists – university students and younger students such as Destiny. The Mongolian Altai mountains are “a spectacular place to do that,” he said. “It is a beautiful laboratory that intersects geology, climate science, glaciology and human culture.”

The research team was a collaborative, intergenerational group. Besides Destiny, it included three students from the University of Maine—Peter Strand, a Ph.D. candidate, Mariah Radue, who is beginning her graduate work, and Nathan Norris, an undergraduate student. The group was joined by Ninjin Tsolmon and Purev-Ochir Purevdorj, two geology students from the Mongolian University of Science and Technology. Putnam was using what he calls a cascade model of education where the more senior students teach the newer students, but all students end up learning from each other.

"I’ve always believed that getting out into the field is the best way to learn,” Norris said. “This is the most intensive field work I have done, and this is priceless.”—Nathan Norris

As part of this research, Destiny said she learned some very important life lessons—avoid walking on wet stones and prevent blisters. And she was able to do “actual sampling.” She used a rock drill, took measurements for the length, width and height of the boulders, and mapped a moraine using a handheld GPS device. She took charge of taking pictures of the rocks for making 3D renderings later, using a camera extended on what is “basically a selfie-stick,” she said. “But it is a very extreme selfie stick. A mono-pod for science, that’s what we’ve been calling it.”

Destiny helped with the selection of key samples and helped look for important qualities of the rock. “Did it have a smooth and polished surface” that indicated it had been embedded in a glacier? “Did it have a quartz vein? That’s what we were looking for.”

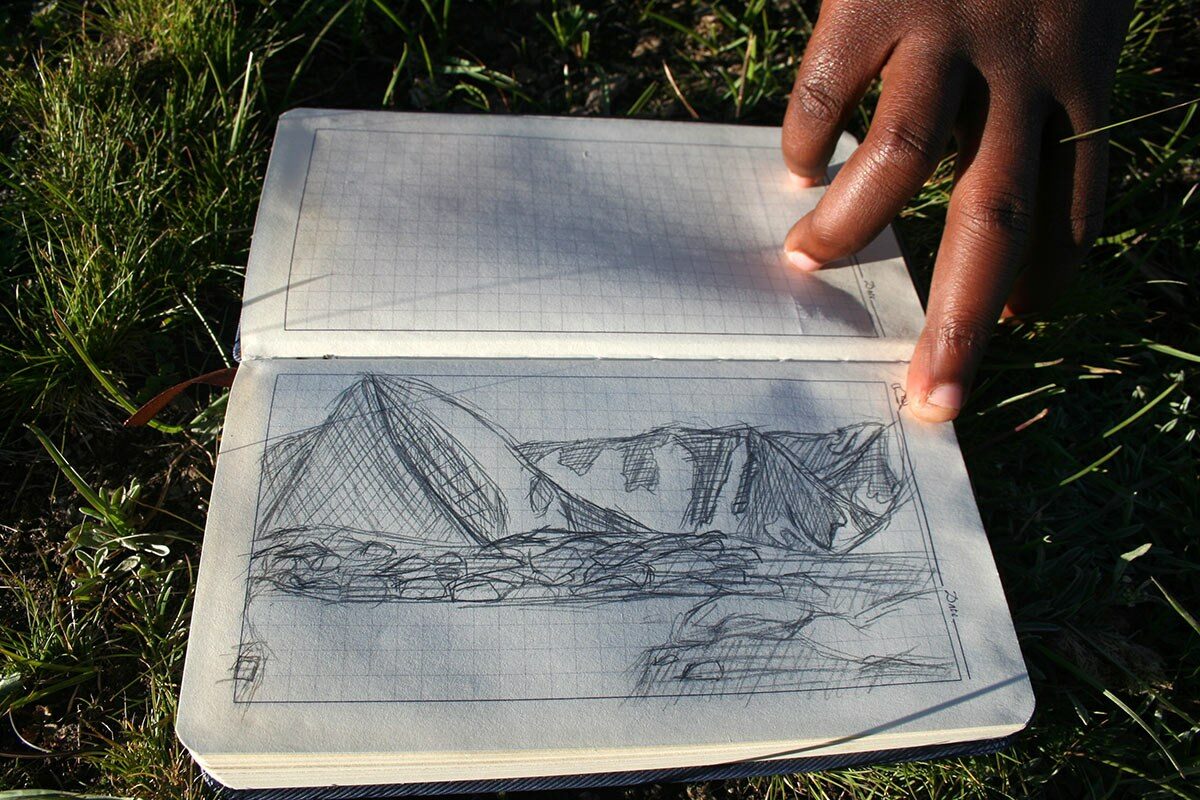

Destiny kept a field journal, in which she drew images of the landscapes, the samples, and other aspects of the research. Stevens and Putnam encouraged the sketching. Photography is great—especially the high quality images taken by Destiny. But the image is still filtered by the current light. “When I take the time to draw something in the field it forces me to analyze that sample,” Putnam said.

Destiny was picked to go on this trip after meeting with Putnam in the spring, writing an application and essay, and after an interview with Stevens, who made the decision. It’s never clear how students will do in a backcountry, field-work setting. Putnam said that many expect a supreme adventure, but the truth is the trips can be an exceptional amount of work and very uncomfortable at times. By choosing Destiny, Stevens “really hit a home run,” Putnam said.

At the outset, Destiny compared the trip to winning a grand prize at the carnival. At that moment, her concept of climate change and glaciers seemed far away from her life experience, mostly in Chicago. On this trip, she was able to be very close to a glacier. “It was interesting to see it in real life versus in a movie or a book,” she said. Her favorite experience of the trip was sampling boulders to date when they were released by the grip of the ice. “Drilling the holes and taking the hammer and shims and wedges and actually hammering the sample out, that was really great,” Destiny said. (Her only mild complaints about the trip were being cold and the flies. As Stevens put it, “she hates flies”.)

Destiny also impressed her teacher with her openness to the cultural aspects of the trip, eating foods—cabbage, home-made yogurt, and the tongue, cheek and ear of a lamb — she had never had before. “She made the most hysterical faces,” Stevens wrote in a blog. Destiny even ate marmot, a local rodent specially prepared for us as a surprise.

The marmot was roasted on the outside and slow-cooked from the inside with red-hot stones heated on a fire. The stones and the meat is placed inside a pressure cooker with seasoning. “I don’t think I’ve ever eaten a rodent, but I don’t feel terrible,” Destiny said after dinner. “It was delicious.” Destiny will be presenting the results of her work in San Francisco at the American Geophysical Union conference later this year. “I want to present the findings in the best light that I can,” she said.

"Even though I’m new at this, I know it’s extremely important to document climate change.”—Destiny Washington