In May of 2015, Dr. Michael Brumage had just finished a 25-year army career. He was beginning a new life in West Virginia and a new job as a health officer for the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department.

On Brumage’s first day, he met with law enforcement and health department officials from nearby Huntington in Cabell County. They ticked off the multitude of problems surrounding heroin use in the county—drug overdoses, a surge in reported cases of hepatitis B and Hepatitis C, and a growing need for substance use treatment services.

Brumage knew about the opioid crisis in West Virginia and had read stories about Scott County, Indiana, where widespread opioid use led to an outbreak of HIV in an otherwise typical rural community. He didn’t want that to happen in Kanawha, and he left the meeting with a direction: the county needed a syringe exchange. He told his colleagues:

“I’m willing to take this on and make it my priority.”—Dr. Michael Brumage

“That was it,” Brumage said. “No one had any objections and based on that we moved full speed ahead.” In December 2015, with public support for an exchange already consolidated by Cabell County health officials, the county health department opened a syringe exchange.

Today, the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department exchange services hundreds of individuals, and communities across West Virginia are following by championing harm reduction programs. County health departments and local clinics are sponsoring syringe exchanges. In the fall of 2015, President Barack Obama visited Charleston to lead a community discussion on the epidemic, and in February, county health officials gathered for a statewide meeting to discuss harm reduction strategies.

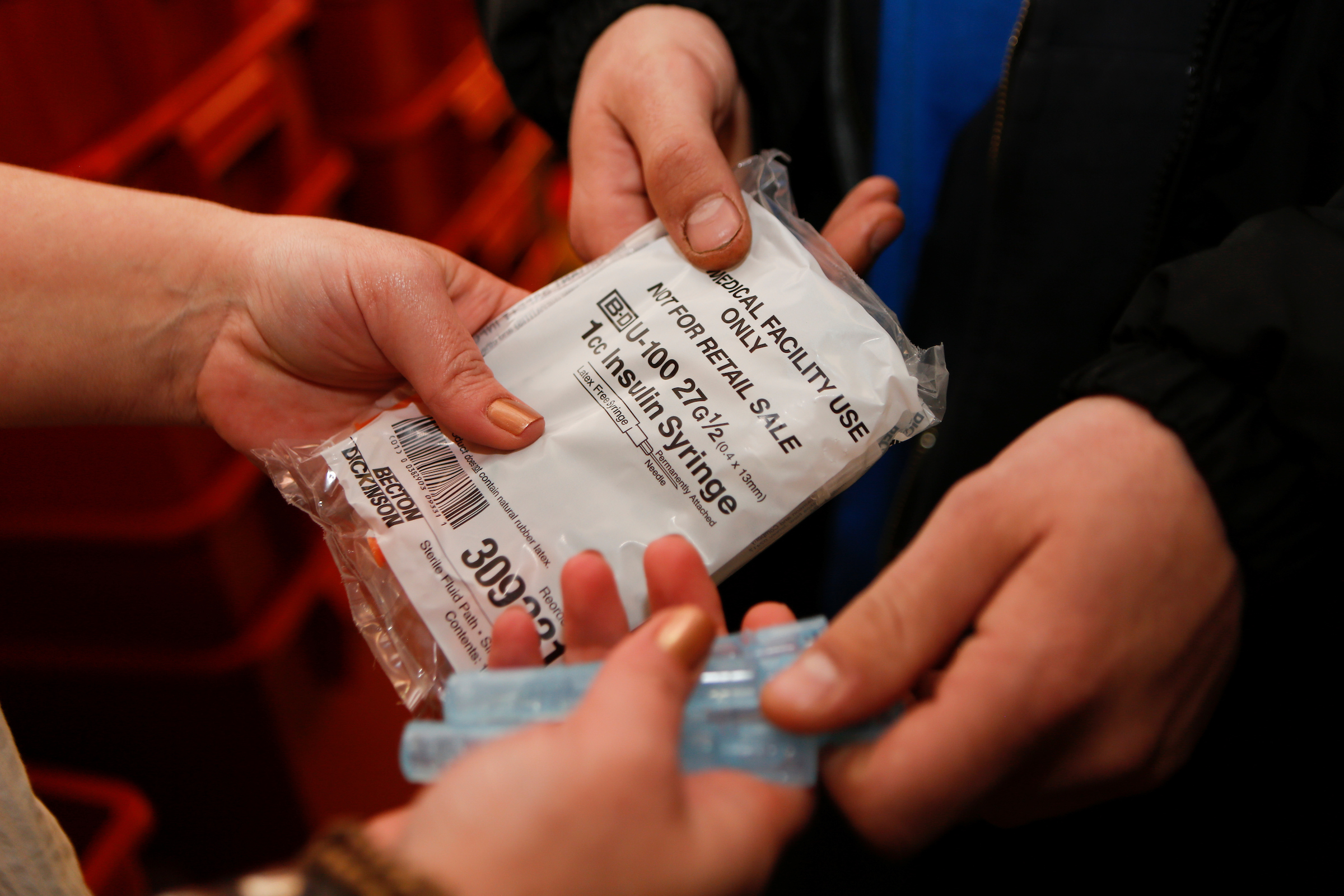

At syringe exchanges, individuals who want clean needles can receive them anonymously. People have access to treatment counselors and other harm reduction measures. All are equipped with Naloxone, which can reverse the impact of an opioid overdose, and some provide overdose reversal kits to individuals who come off the street.

Across the 13-state region of Appalachia, communities have been devastated by the opioid epidemic, which has compounded troubles for a region suffering from industrial decline and rural job loss.

In spite of decades of research that suggests that exchanges prevent the spread of blood-borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C, and harm reduction programs encourage drug users to seek any positive change for their drug use, including access to healthcare and treatment, many conservative Appalachian states don’t allow syringe exchanges.

Daniel Raymond, a policy director for the Harm Reduction Coalition, said that in the past few decades, West Virginia was flooded with prescription pain killers, and many of the pills went to people with chronic pain.

But the pills were addictive opioids. “People became dependent and then there was a progressive movement towards heroin,” Raymond said. “It was kind of a bellwether for what was happening in other places in the country.”

In the United States, more than 33,000 people died from opioid overdoses in 2015—more than any other drug—and the number of deaths has steadily risen during the last fifteen years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In West Virginia, the numbers are even more severe. The state has the highest rate of overdose deaths in the country; for every 100 deaths, three will have been from an overdose. The state’s Health Statistics Center released a report that found 2,900 West Virginians have overdosed on prescription painkillers in the past five years. Washington Post reports that there are so many deaths that officials can’t keep up with the funerals.

Raymond said the crisis has been a “catalyst for officials saying we need to think more broadly about these issues. We need to put more things on the table – that included syringe exchanges. In West Virginia—this conservative state—it’s remarkable.”

The issues that surround drug use have been pushed to the forefront in West Virginia. Emma Roberts directs capacity building services for the Harm Reduction Coalition, where she works with Raymond. She said the culture and approach around drug use is changing.

“It’s no longer a punitive, tough love, abstinence based approach, but it’s a public health approach,” she said. “It enables people to create a culture of inclusion around this issue. It speaks to the wider public health concerns about hepatitis C and HIV.”—Emma Roberts

“The community has realized this is an issue of health, and something that was controversial became less so,” she said.

Often, harm reduction programs also serve as an engagement point for officials looking to connect with individuals fighting addiction. That’s a tactic being employed by the Milan Puskar Health Right, a free clinic operated in Morgantown, West Virginia.

The free clinic is directed by Laura Jones, who wrote the grant for the first syringe exchange in West Virginia—it opened just a few weeks before the Cabell-Huntington Health Department. Health Right offers peer recovery support services, wound care, rapid testing for HIV and hepatitis C, counseling and other harm reduction services. “We have pulled together many parts of harm reduction into one place.” Jones said. “It is one stop shopping.”

The clinic will soon have its second anniversary, and its staff are servicing more than 600 people. They learned early that they couldn’t advertise—the clinic was quickly at capacity.

“Yesterday we had a gentleman come in from the Catholic charity to enroll people in SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits right there at the exchange,” she said. “We are trying to provide as many resources as possible.”

Now, other communities are taking up the harm reduction model. In Jackson County, which borders Ohio, the health department launched its first syringe exchange in February. Amy Haskins is the project director. She’s wanted to bring harm reduction to the area for years. But the health board was concerned about liability and some thought the exchange would promote drug use, a common—if inaccurate—critique.

Haskins kept pressing the issue with local health officials and police. She pointed to the increasing rate of hepatitis C infection as evidence that a new approach was needed. Slowly, people began to see the issue as she did: one of public health.

“It’s been an interesting process,” she said. “We’ve been trying to get over the barriers. Trying to break the stigma and be very conscious of the varying perspectives in our county. We are still the health department and we must serve the community. We cannot drive people away.”

“Now, more than ever, it is important to us to see county health departments and community based organizations take the lead in establishing syringe access programming,” said Mary Pounder, the program director for the Comer Family Foundation. For more than three decades, the Foundation has supported harm reduction-centered syringe exchanges as a means of controlling transmission of blood borne diseases. “We have been particularly interested in statewide collaborations and rural areas, funding four West Virginia syringe access programs in response to the opioid epidemic.”