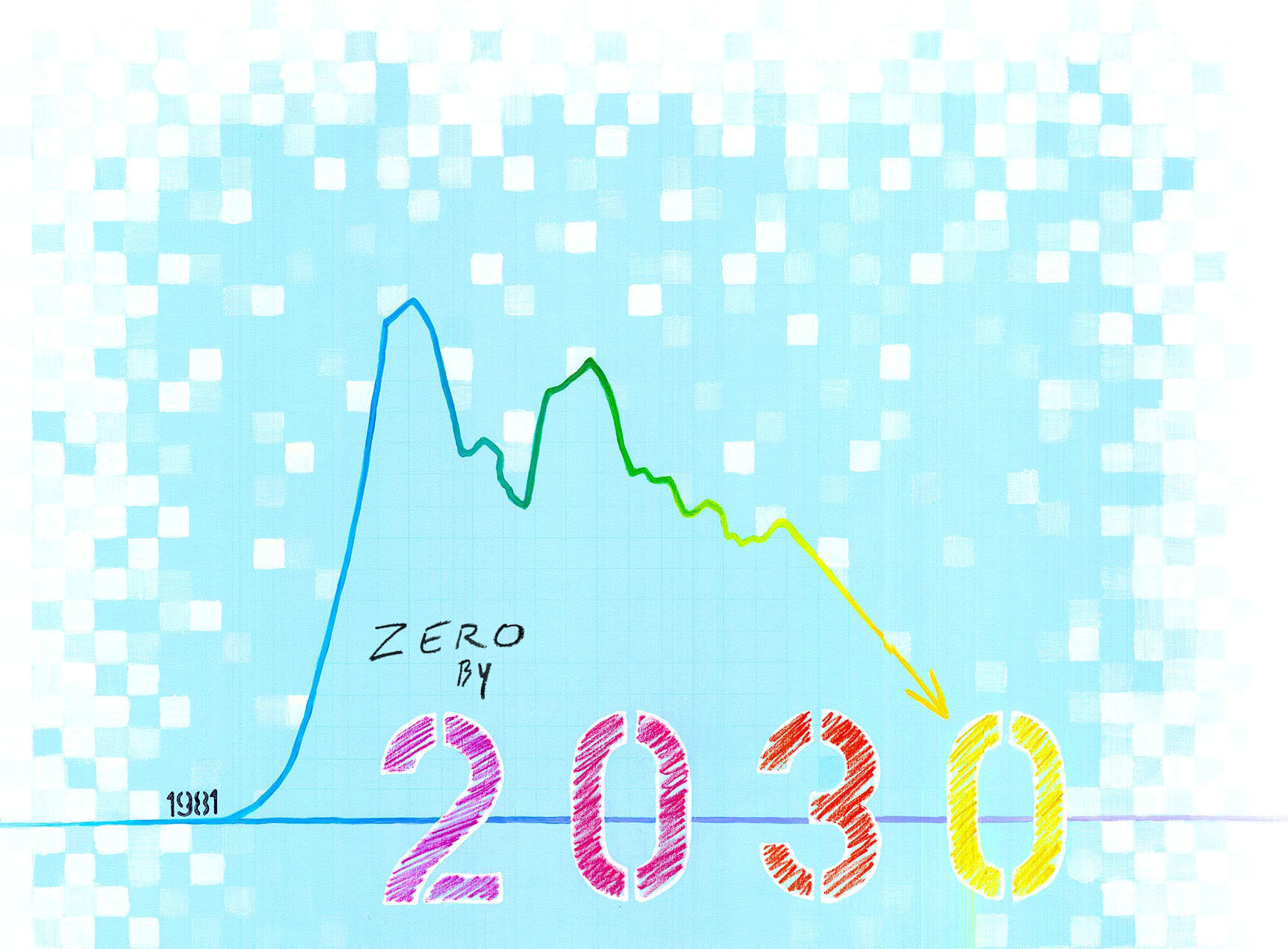

Getting to Zero is a state-wide initiative to end the HIV epidemic in the state by 2030.

In 1981, a cluster of medical cases of immune deficiency led to the deaths of 121 men in the U.S. Shortly after, similar cases began to arise in all of America’s major cities. In Chicago, many early cases were seen by two young physicians, David Moore and David Blatt, a couple that was also working together at Illinois Masonic Hospital. Many of their close friends came to them with unusual symptoms—markers of what was then called GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency). After attending a conference at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York to learn and share knowledge with other doctors, they opened up Unit 371 at Masonic to care for patients suffering from what would soon be named HIV.

“We worked with administrators and voluntary nursing staff to create a unit to cluster services for patient care in a humane, compassionate, and empathic environment,” shares Moore. “There we could provide expert care and combat fear with education, including about universal precautions that appropriately isolated the virus (in potentially infectious bodily fluids), rather than isolating the person with the illness.”

Without even a diagnostic test to identify the virus until 1985, no one knew if they were next in line for sickness, and an inevitable, horrible death. As the years went on, the effect of HIV expanded to impact nearly every community and population across the globe. The World Health Organization reports that the epidemic has claimed about 35 million lives since its discovery, and 940,000 in 2017 alone.

While Illinois is hovering around the median for HIV transmissions amongst the states, it remains vulnerable. In 2015, more than 35,000 people were reported to be living with HIV within the state, with more than 1,300 new diagnoses the following year.

Throughout the country, initiatives have been cropping up to identify strategies and practices to eradicate HIV transmissions and provide better healthcare to those living with HIV. The Getting to Zero Illinois (GTZ-IL) plan has been in development for three years, and it was released in May 2019 to put forth the bold and tangible vision that Illinois will have zero new HIV cases by 2030.

“A large part of our plan addresses health equity and strategies in place for all specific populations… making sure all communities in IL are able to GTZ by 2030”—Brian Solem

Antiretroviral therapy became available (but scarce) in 1996, meaning that each diagnosis no longer meant certain death. Since 2012, medications have been readily available that reduce or eliminate risk of HIV transmission as well. Reports of new cases have gone down, but not quickly enough. And, while overall trends are down, the CDC reports that within communities of color (Black, Asian, Latinx), trends for diagnosis are stable or increasing. The GTZ-IL plan seeks to address these imbalances, making sure that information, support, and medications are available to those who need it, regardless of their ethnic identity, geographic location, or economic status. Their stated goal is to reduce transmissions in Illinois to functional zero by 2030 so that people already living with HIV can maintain their health, and those who are HIV-negative do not acquire it.

What does it all mean?

- Getting to Zero: zero HIV transmissions and zero people living with HIV who are not engaged in medical care

- Functional zero: 100 or fewer new HIV cases a year means the epidemic cannot sustain itself

- Antiretroviral Therapy (ART): prescribed medication for people living with HIV to reduce the presence of the virus in their bloodstream (or medication for HIV-negative people to prevent transmission, like PrEP)

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): approved by the FDA in 2012, the anti-retroviral marketed as Truvada is a prescribed drug for anyone who is at risk for HIV; it has proven to be more than 99% effective at preventing infection when taken daily

- Undetectable: person living with HIV whose ART has been successful enough to make the virus undetectable (less than 200 copies per ML) in their bloodstream

- U=U (Undetectable = Untransmittable): phrase highlighting that people living with HIV who are undetectable are unable to transmit the virus to a partner through sexual contact

The GTZ-IL campaign emerged to ensure equal access to care, specifically including communities that may slip through the cracks of traditional outreach or marketing. Led by a 19-person steering committee of key community and government partners, various teams have spent the last few years holding town hall meetings and focus groups in 26 venues throughout the state to learn the specific challenges and needs of differing communities affected by HIV.

Despite PrEP being readily available and covered by most insurance plans, Medicare, and Medicaid, not everyone knows that they may be at risk and eligible, where they can get it, or how to take it properly. This results in a heightened inequity in HIV transmissions. While Black people represent 14.2% of the population of Illinois, they represent 46.6% of people living with HIV in Illinois. Black women are 18.4 times more likely to contract HIV than their white female counterparts. Latinx women are 4 times more likely to contract the virus, and Latinx men are 2.5 times more likely than their white counterparts.

“A large part of our plan addresses health equity and strategies in place for all specific populations...that statistically have a greater incidence of HIV year after year...We’re making sure all communities in IL are able to GTZ by 2030, not just white communities,” says Brian Solem, Director of Communications for AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC), and a member of the GTZ-IL steering committee.

The plan, available on the GTZ-IL website, outlines six major domains for research and action:

- WORKFORCE: Foster new approaches and adapt to evolving needs

- HEALTH CARE: Enhance care and increase access for people living with and vulnerable to HIV/AIDS

- EQUITY: End health disparities associated with race, ethnicity, sexual and gender identity, age, residency status, and lived experiences

- EFFICIENCY: Coordinate activities to expand the reach of necessary services, and strengthen the HIV service delivery system

- LINKED CONDITIONS: Increase access to treatment for mental health, substance use, STIs and viral hepatitis

- SURVEILLANCE: Improve data gathering, sharing and exploration to benefit systems of care

“Often HIV research including Black subjects is an ivory tower situation where data is being collected, produced and reported, but only in academia, and doesn’t actually affect change within the community,” shares Erik Glenn, GTZ-IL steering committee member and Executive Director of the Chicago Black Gay Men’s Caucus. One of the ways he accomplishes this is by examining the location of health resources in metro Chicago, to make sure that they are within easy reach of predominantly Black communities on the South and West sides, and via public transportation.

AFC’s Director of Special Projects and Planning, Roman Buenrostro, took initiative in reaching out to the Latinx community. He identifies the two most pressing concerns as “identification of risk for vulnerable individuals, and the provision of quality services in Spanish language.” Several of the town hall meetings throughout the state were conducted in Spanish, and in preparing a Spanish translation of the GTZ-IL plan, efforts have been made to make the language regionally inclusive, reflecting the diverse heritage of Illinois’ Latinx population.

Outside of the metro-Chicago area, finding specialists who are knowledgeable about HIV treatment and prevention can be a challenge. Clinics are often housed within educational institutions and hospitals, but vulnerable communities are not always engaged with higher education or specialized medical care. Candi Crause, another steering committee member for GTZ-IL, serves as the Director for Adult Services in the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District. She explained that marketing in the metro areas, which normally centers around LGBTQ events and spaces, wouldn’t translate well to the Champaign-Urbana area. With no gay-identified bars, she has learned to diversify her marketing efforts to promote Truvada as PrEP and other health services. Her priorities include flyers in mainstream bars, community centers and the UIUC campus as well as ads on buses traveling around the campus and town area.

Another community often missed in PrEP or HIV-treatment messaging is the transgender and gender non-conforming population. Lee Andel Dewey leads a group called CommunityCave Chicago, a collection of people that were assigned/designated female at birth and identify as anything other than cisgender. It took Lee (who uses gender-neutral pronouns) years for them to understand that they might be a good candidate for PrEP. Upon learning about it, Lee started the process to assess candidacy. PrEP prescriptions require initial bloodwork to confirm HIV-negative status, and it was in that testing process that their HIV infection was diagnosed. In the years since, Lee has become vocal about their HIV status and even more of an advocate for education, testing, and access to Truvada so that others don’t have the experience that they did.

While the HIV epidemic is not yet under control, the biomedical resources to end it are available to us. The Comer Family Foundation supports the efforts of GTZ-IL to inform our social and medical institutions how best to deploy their resources to reach the goal. To get to zero, Brian Solem knows that the final plan has to “not be a top-down plan, but a plan that has investment on every level of every spectrum of people in Illinois.”