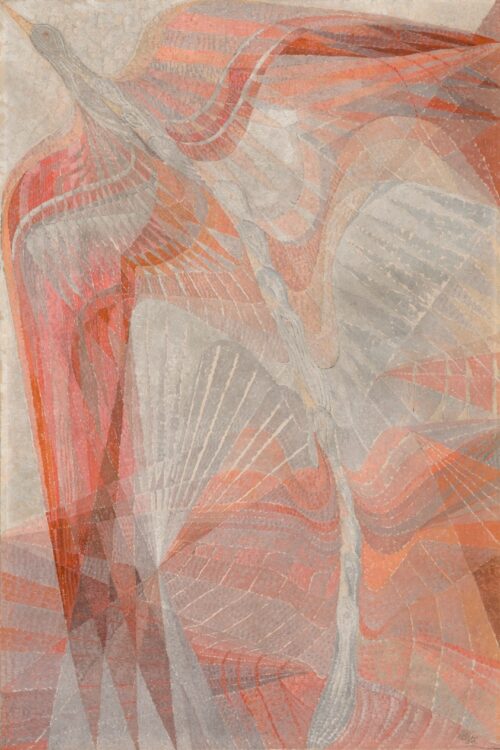

Remedios Varo (Spanish, 1908–1963) Exploración de las fuentes del río Orinoco (Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River) 1959 Oil on canvas 44.5 × 39.5 cm (17 5/16 × 15 9/16 in.) Private collection © 2023 Remedios Varo, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid Jamie M. Stukenberg, Stukenberg Photography

Our founder Francie Comer’s long relationship with the Art Institute of Chicago celebrated her belief in the museum’s role to offer a world of culture and ideas for all Chicagoans to enjoy.

We were honored to have the chance to speak with curator Caitlin Haskell upon the opening of Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, a show noted for its otherworldly beauty, curiosity and provocative humor. Caitlin is the Gary C. and Frances Comer Curator in Modern and Contemporary Art and director of Ray Johnson Collections and Research. A scholar of 20th-century painting and sculpture, her exhibitions and publications have addressed the production and critical reception of modern art in Europe and the Americas.

Can you talk about the importance of expanding the traditional canon of art history for today’s museum goers?

It’s interesting, as a curator working on 20th-century painting and sculpture at the Art Institute, a lot of times I’m working pretty squarely within the canon: Matisse, Picasso, Duchamp, Magritte, Kandinsky, etc. But then there are other moments when we are able to introduce figures into the collection or into a gallery display who, in most cases, also had a significant role in the art of their time, but are much lesser known today for one reason or another.

In the very first gallery that most visitors enter in our display of International Modern Art, there are icons--Picasso’s Old Guitarist, the Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Matisses's Bathers by a River. But there are also works by Amadeo de Souza Cardoso and Émilie Charmy, for example, who are obviously far from household names. Those two works by Cardoso and Charmy, interestingly enough, both entered the Art Institute’s collection in the 1930s. If you were building a collection of advanced European modern painting in the 1910s and 1920s, there was reason to place both of these artists in the context in which we show them. And it’s really more a matter of historical circumstance, rather than anything having to do with the intrinsic quality of their work, that makes Cardoso and Charmy not as well-known as their contemporaries in that gallery. Cardoso happened to die of Spanish Flu while he was in the prime of his career, and Charmy, well, she did receive some critical attention during her lifetime. But she was a woman working at a time when women weren’t given the same opportunities as male artists, weren’t taken as seriously by critics, didn’t command the same prices, etc.

So, as a historian, I’m always trying to expand the field of information my work draws upon. You never want to be working from a shorthand or a subset of what occurred during your period of study, which is one way of saying what a canon is. You want to be striving for, let’s say, a less-abridged version of what took place, because an unabridged version simply isn’t possible. And as you do that, and expand your points of reference, there is the benefit of discovery, freshness, seeing works that surprise and delight you, encountering works that can’t fit neatly into any style or explanation of what modernism is alleged to have been. That is always enormously energizing.

And then, of course, because most of the writing about modern art was so focused on particular cities, centers, and collectors, as soon as you move away from that very encapsulated view of modernism, your history starts to become much more representative, actually. It’s more representative of the public viewing art today, and it’s also more representative of what actually happened.

So, that’s a very long winded way of saying that it's more interesting and also more accurate when you can move away from the canon. But the paintings in the canon are pretty incredible too. You need to be able to work with both.

Remedios Varo (Spanish, 1908–1963) Hallazgo (Discovery) 1956 Oil on hardboard 78 x 69 cm (30 11/16 × 27 1/16 in.) Private collection © 2023 Remedios Varo, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid Jamie M. Stukenberg, Stukenberg Photography

There are a lot of discoveries to be had in our galleries for the person who is curious to learn more, whether they are coming to the Art Institute for the first time or returning week after week.—Caitlin Haskell

What kinds of things is the AIC doing to bring overlooked artists to the forefront?

My colleagues and I in Modern and Contemporary Art are always actively doing this type of research in exhibition-making, acquisitions, collection presentations, all phases of our work as curators. We’re constantly learning about the artworks in our holdings, and we’re also strategically adding to those holdings with purchases and gifts.

Sometimes you can find an overlooked artist in storage, or perhaps an artist who was once popular, and contributes again to a conversation happening now. This was the case recently with a painting by Loren MacIver, a work that the museum purchased in 1953, that we just brought back on view in August. Likewise, we have a painting by Erika Giovanna Klien that has been on view regularly of late. She is a lesser-known name, certainly, but the work is strong and we’ve shown it in a few contexts. In one of my favorite galleries, we have major works by Franz Wilhelm Seiwert and César Domela shown with Mondrian, Moholy, and Klee. Seiwert was a purchase in 2021 and Domela was made a promised gift to the collection in the same year, and I have to think that even if you have not heard of Seiwert or the Cologne Progressives, you sense the ambition of his painting, and likewise Domela’s relief is a supremely fascinating artwork. So, there are a lot of discoveries to be had in our galleries for the person who is curious to learn more, whether they are coming to the Art Institute for the first time or returning week after week.

And then, of course, there’s Remedios Varo. When you walk into that exhibition, the vast majority of people are encountering the artist’s work in person for the first time. We are extremely proud of this exhibition, which is the first presentation of Varo’s work in the US in more than 20 years, as well as the catalogue. And although we do not yet have Varo in the museum’s collection, the Art Institute’s surrealism holdings contextualize her work very nicely. We could point to Alice Rahon, Wolfgang Paalen, Leonor Fini, Leonora Carrington, Oscar Domínguez, who are all on view upstairs from the show. Some of these figures have been in the collection for years, but others are newer and we’re building the context where Varo is at home, in a sense. It’s a type of Surrealism that has to do as much with Cold War experience in the Americas as it does with Europe in the 20s and 30s.

With Remedios Varo’s work, there is often a sense of everyday life coming through, whether that’s in her choice of imagery – the sewing kit that has become animated, the attention to clothing and living spaces – and also in her choice of materials.—Caitlin Haskell

Work/life balance is an issue today, but very different constraints applied in the past. How were women artists aligning art-making in their everyday lives?

Unfortunately, I am probably not someone who should speak about work/life balance. It’s a struggle. But with Remedios Varo’s work, there is often a sense of everyday life coming through, whether that’s in her choice of imagery – the sewing kit that has become animated, the attention to clothing and living spaces – and also in her choice of materials. You can sense the inspiration in a work like Homo Rodans. What will I do with these chicken bones? I also think that in our exhibition a sense of everyday life comes through in the display of notebooks. There are drawings next to notes about personal accounting, how much she was getting paid for a painting, etc. I think there is a sense of obsession in a positive way in Varo’s work. She found something she loved, and her life flows into it, people she cares about start to be included in the work, whether that is Walter Gruen in Taurus, Juliana Gonzalez in Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst, Mario Stern in relation to Vagabundo, or even Varo herself symbolically, in a work like Useless Science or The Alchemist.

Original Interview: September, 2023

A self-guided tour of the 20th-century galleries

See the work Haskell mentions in the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. Start with Remedios Varo: Science Fictions on the 2nd floor. Then, on the 3rd floor, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso and Émilie Charmy can be found in Gallery 391 followed by Erika Giovanna Klien in Gallery 392 and Loren MacIver in Gallery 398. As you move throughout the floor, you will find major works by Franz Wilhelm Seiwert and César Domela alongside Mondrian, Moholy, and Klee.

Rhythm of Bird Flight, Erika Giovanna Klien, 1935

Émilie Charmy, French, 1880–1974, L’Estaque, c. 1910, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

César Domela, Dutch, 1900-1992, Relief no. 12B, 1936, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Alice Rahon, French, active Mexico, 1904–1987, Self-Portrait and Autobiography, 1948, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Wolfgang Paalen, Austrian, 1905–1959, Untitled (Fumage), 1938, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, German, 1894-1933, Mural for a Photographer (Wandbild für einen Fotografen), 1925, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago