In 1958, as a sophomore at Tufts University, George Denton traveled to Antarctica for the first time. Peering out the window as the sixth and final leg of his journey came to a close, Denton got his first glimpse of the distant land.

“The first sight I saw was Mount Erebus out the plane window. I had never really seen the Arctic or Antarctic, and I don’t know how to describe it. It was an interesting place: a polar desert and polar glaciers. It's just like going to a new world, really. I became interested in what it all means.”—George Denton

That first trip led to another, and many more in the years to come. These formative excursions influenced Denton, now a professor at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute, as he became one of the most accomplished climate scientists of our time. As a scholar of abrupt climate change, he studies the history of glaciers seeking clues as to when, why, and how they transform. This research is crucial in charting the future of the earth’s climate, and understanding how we can alter our course to protect the planet.

Denton, a formidable thinker, knew that his questions depended on building a large community to solve them together. Over the course of his career, he has set out to not only research and publish, but to construct an academic family that works collaboratively. This reference to family isn’t made lightly—members of Denton’s tribe speak about their relationships as if they are all on a family tree. The unifying factors are clear: respect for the Earth, respect for each other, and respect for the process of learning together. There may not be a better model for a productive life than what Denton has built for himself and others.

To say Denton’s inquiries are ambitious is an understatement. As Brenda Hall, a former student and now a fellow professor at the University of Maine says, “he goes for the big problem.” George’s reach goes far beyond his research and his published articles. He identifies big questions and inspires others to join him in relentless pursuit of their answers.

Our first conversation took place in January 2020, only a few days after I was introduced to his work. It was rushed because he was leaving soon for the glaciers of southern New Zealand and we wanted to speak before his departure. Over the course of an hour, I was challenged and instructed on the history of Antarctic research and glacial studies. I emerged from our initial interview with a reading assignment of three books. George is a teacher through and through and brings that into every interaction he has with others. He became my instructor for the length of our meetings, and his manner of storytelling was truly rapturous.

The Formative Years

As a child, George lived in the northern suburbs of Boston. His father was a civil engineer—designing and building major roads and highways. His mother stayed home to care for him and his two younger sisters. He didn’t grow up transfixed by science, but he loved ice hockey as well as camping and canoeing excursions with his scout troop.

These experiences led to Denton’s adaptability in field research later in life. When asked how he handled the challenges of extreme weather in the field, since I personally would find that intimidating, he responded, “Antarctica is not extreme. Antarctica is the easiest field work on Earth.” Naturally I asked him to name field conditions he did consider extreme. “I never found any. Most of it is pretty easy. I suppose some people have found challenging field work, but I never did. It's not as though it was difficult, and it was easy for me, it just wasn’t difficult.” His early training and experiences with the scouts clearly prepared him for a life he couldn’t have imagined at a young age.

When he first joined the workforce, he spent his summers in construction. He helped to build what is now Route 128 in the greater Boston area to pay for his studies, and in 1957, enrolled at Tufts University nearby.

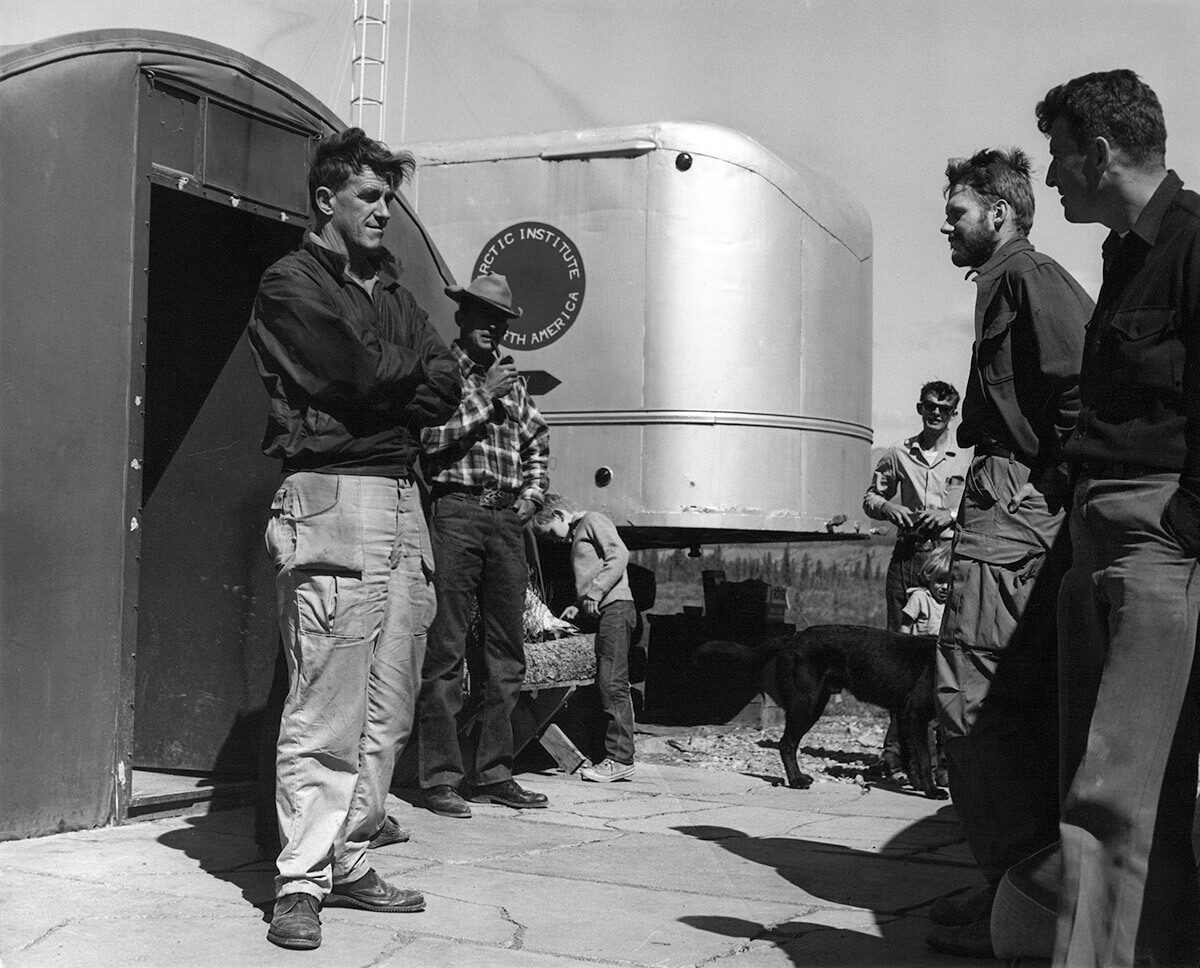

Each day during orientation week, a different scholar presented a lecture on their area of expertise. Bob Nichols, a geology professor, spoke about Antarctica, ice sheets, and the value of research in polar regions. It was enough to get Denton to enroll in his intro course, and the following year George joined Nichols’ research trip to Antarctica.

George’s studies progressed, and he earned his Masters and Doctorate degrees in geology from Yale. A few years after receiving his Ph.D., he accepted a teaching position at the University of Maine, where he remains to this day. One of his colleagues, Professor Joellen Russell (University of Arizona) described the power of this choice:

He may have fewer resources at University of Maine than he would elsewhere, but making sure students have access to him is critical. George feels that his students, regardless of their background, deserve a world-class education, and he makes sure they get it if they work for it.

Inspiring Students

Given his academic status, one would expect George to work closely with top graduate students studying geology and climate change. In fact, he is often the draw that brings those students to the school. But in addition to his mentoring responsibilities and high-level research, he teaches a large undergraduate introductory course—Humans and Global Change—that allows him to work with younger students.

One of George's most notable traits is his remarkable ability to deflect attention away from himself. Instead of touting his accomplishments, he adores championing the work of those around him. For further insight into George Denton as a person and all that he has achieved, I spoke to some of the scientists closest to him. In addition to Joellen Russell and Brenda Hall, I connected with former students who have gone on to run their own research programs—Thomas Lowell (University of Cincinnati) and Aaron Putnam (University of Maine).

Fostering independent thought is a clear priority for Denton, but he also maintains very high standards. Putnam described the intimidation he felt in his first interactions with George as a teacher: “He was pretty tough. You knew you had to be very disciplined to work with George. And he would not hesitate to let you know if you were behind the eight ball.”

Lowell related one of his first encounters with Denton. Upon returning graded exams to his students, George displayed two chalkboards full of words that had been repeatedly misspelled. If students repeated those errors on the next exam, George would lower their score by a full letter grade. Lowell related that spelling and grammar were never his strong suit, but this experience helped him to understand the value of writing. The discoveries you make and the work you do only have maximum impact if you can communicate them properly to others.

On campus, Denton isn’t the type to hang out in the coffee shop and chat, but he makes sure his presence is felt, frequently stopping by the graduate student offices. He checks in on their work and challenges them to think deeper about the questions they hope to answer. He knows his students, cares about them, and creates opportunities for them to succeed.

Putnam talked about the impact Denton had on him: “The beauty of it is he really teaches people how to become independent thinkers, not just to learn a method or something, but really to think about how the world works. And it's almost infectious...he just is always brimming over with ideas that are related to really large-scale problems in science.”

Flourishing in the Field

For a researcher like George, large swaths of time are spent in the field on research excursions, often for months at a time in far-flung lands. This is where George shines, and is able to focus intently on the work at hand.

Spending time in remote Antarctica, Chile, New Zealand, and China sometimes requires uncomfortable living. Denton’s trips often have him sleeping in tents or on research vessels cutting through ice in polar seas. These conditions bring out some of the best in George, according to Putnam: “The field George is a very easygoing, insightful guy, and a lot of fun to be around and with an infectious enthusiasm about the science… He's more reserved in the office, but in the field, you can tell that's where he's really, truly happy.”

By his count, he’s taken over 150 students to Antarctica, not to mention research trips to New Zealand, China, and Chile. This is an expensive endeavor, but he’s been able to find funding through grants and fellowships.

Over the last two decades, Denton has partnered with the Comer Family Foundation to help fund field research for students. When founder Gary Comer was looking for ways to have impact on abrupt climate change research, he was introduced to Denton, who helped Gary better understand the science and the resources needed to further the work. For some background about this partnership, read about the Comer Fellowship they crafted together.

Even with significant funds at his disposal, Denton still has to be choosy about who he selects for field research. With large introductory classes, I asked him how he identifies students with the most potential.

George’s students are taken into the field to be independent thinkers who challenge his own preconceptions and assumptions. The scientific method instructs students to identify a hypothesis, collect data to prove or disprove it, and analyze the results in relation to that initial question. According to Lowell, Denton’s process is more complex. He sees a problem not in relation to a single question, but from all sides. He asks to be challenged, and to debate the big theories and approaches to understanding climate change. It isn’t unusual for him to forget about lunch because he is so engaged in data collection and the creative thinking required to solve problems.

“We point out the problems and we prompt [the student researchers] to ask the questions and think of how to approach the answer. They shouldn’t tell us right away but take a couple of days to think about it, and then tell us their thoughts. We make them think this way throughout the whole exercise.”—George Denton

Family Building

With a curriculum vitae as robust as Denton’s, a natural line of questioning led me to ask him what aspect of his research he is most proud of. “I’m not particularly proud of much of it.” he replied. “The thing I'm proud of is starting people in the field, like Brenda or Tom or Aaron. Seeing them get jobs—just seeing them succeed.”

One of the threads that permeated the interviews I conducted was the sense of familial connection surrounding Denton. He acknowledges this saying “Well, they call it that…They claim that I'm the head of a family and they align themselves where they are in the family, all their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren…They are my professional family. That’s the way I look at it, too.”

Something that George tends to keep quiet about are the personal things he does to support the people in his chosen family. One researcher told me they were fairly certain that George paid for their medical insurance while they were a graduate student and had trouble covering the expense. They simply know that the bursar said the bill was paid and it needn’t be a worry moving forward.

The value George places on those around him is as much of a contribution to the future of science as his own work. Denton possesses an exceptional ability to explore complex questions, uncover intricate answers, and communicate them in a relatable way. He creates space for those around him to do the same. Lowell may have summed up Denton’s work the best: “George has a way of mentoring people that inspires them, promotes them, makes them work, and gets the best out of them.”

Looking Forward

Denton has won a number of prestigious international awards and published nearly 200 papers and articles. I was amazed to discover that there are two sites in Antarctica—the Denton Glacier and the Denton Hills—named in his honor. Denton, however, countered this with his signature humility.

Denton is just as disinterested in retirement as he is in fame. Russell explains his continued work ethic:

Since retirement isn’t on his roadmap, I asked him what’s next in abrupt climate change research, and what questions he’s asking right now.

As he continues his research and his teaching, Denton quietly fuels work that may hold the answer to our planet’s future. He’s an imposing figure both in life and in his field, but his gentility and quiet power are central to his eminence. If you’re not embedded in climate change research, George Denton is likely not a household name. But perhaps, he should be.